Before, we demonstrated:

That the ultimate purpose of all human beings is to Flourish, not to be Happy;

That Happiness as the ultimate end corrupts the classical virtues;

That the pursuit of Happiness, as we know it, makes one ineffective or slave-like;

That the actual virtues are Excellences (aretai), unique to human beings;

And that the Excellences, practiced and perfected, will always result in Flourishing (Eudaimonia)

The ethics co-opted and distorted by Christians . . . and the ethics fought by the enlightened philosophes . . . are not Aristotelian. There is not a booming voice that is giving us commands, nor abstractions that hang throughout space and time, instructing us on how to be “Good.” There is only Nature, and Man’s Nature; whose peak is a type of Excellence.

It is something we know in our bones.

In the historical figure, it is obvious; FDR and Joan of Arc. But it appears in the common and all over too. We see it in our friends, in our siblings and co-workers—in strangers at a gym or at a well-lit cafe. We see it in our children, all of a sudden, when they hand us a well-made drawing; and we see it in ourselves for a short duration, bemused as it melts back to silence.

As an ethic, Flourishing completes one; as an ethic, it catalyzes.

The tension that builds through the Nicomachean Ethics leaves us with the sense that “something” should happen. That some flowering or rip of light should result of acquiring all the virtues. Beyond mere Flourishing (Eudaimonia), we expect a “type” of human to emerge.

And it does.

The Great Souled Man is a culmination. He (or she, in my view) is the manifestation of perfect Courage, Temperance, Ambition, Justice, Patience, Liberality and all the rest. But the more that Aristotle describes him, the less we see him as the aforementioned. Something is amiss.

Aristotle is succinct in defining Greatness of Soul:

”He who deems himself worthy of great things and is worthy of them is held to be great souled [...] he who is worthy of great things while not being worthy of them is vain [...] He who deems himself worthy of less than he is worth is small souled [...] And most small-souled of all would seem to be the person who is in fact worthy of great things but does not deem himself so [...]

The great-souled man, then, is an extreme in terms of greatness, but he is in the middle in terms of his acting as one ought [...] Greatness of soul seems to be like a crown of the virtues, for it makes them greater and does not arise without them. For this reason, it is difficult, in truth, to be great souled [...]”

— Nicomachean Ethics (4.3)

Some of the language here is subtle, but where Aristotle says “he is in the middle in terms of acting as one ought,” he means that the Great Souled Man is virtuous. And to be virtuous in Aristotle’s ethics means to occupy a middle point between two extremes.

Courage is between recklessness (excess) and cowardice (deficiency). Liberality is between wastefulness (excess) and stinginess (deficiency). So on and so forth. It is interesting that Aristotle believes the result of occupying every single mean is an extreme . . . an over-great person. We, by contrast, would expect an excellent moderate.

“He will take pleasure in a measured way in great honors and those that come from serious human beings, on the grounds that he obtains what is proper to him [...] As for honor that comes from people at random, or small honors, he will have complete contempt for them, since it is not of these that he is worthy [...]

He will surely be disposed in a measured way toward wealth and political power as well as all good and bad fortune [...] he will be neither overjoyed by good fortune nor deeply grieved by bad fortune. For he is not disposed even toward honor as though it were a very great thing [...] To him for whom honor is a small thing, so also are these other concerns [wealth and political power]. Hence, the great-souled are held to be haughty.”

Here we meet with the first contradiction. The Great Souled Man is concerned with great honors . . . but also views honor as “no great thing.” This slip will be important later.

"The great-souled man justly looks down on others (since he holds a true opinion of himself), [...] The great-souled man is not one to hazard [minor] dangers and he is not a lover of danger either, since he honors few things. But he will hazard great dangers, and when he does so, he throws away his life, on the grounds that living is not at all worthwhile.”

This is one of the most bizarre passages in Aristotle because he makes a point to argue three things: (1) That there is no afterlife in which to Flourish after death; (2) That being alive and materially well-off are prerequisites for Eudaimonia, and; (3) That you can never know if one was Eudaimon until they’ve lived completely. He therefore anchors his Ethics squarely in this world, and they require, at base, a long-term physical wellness. The arc of a life must then be virtuous (as we defined it earlier), and increasingly successful.

Success, over time, is required because in the context of a polis (city-state) . . . this is the only way to meet with all the situations that allow one to totally Flourish (war, public works, holding office, aiding friends, etc.). Even in the case of “war,” which we can render as “conflict” generally, Courage calls for fighting well AND for preserving one’s self. Otherwise, it trends into one of the vices: Recklessness (the excess), which means one is no longer “virtuous.”

It is strange, then, that Aristotle’s ultimate type wants to die. He seems eager, in fact, to terminate his Eudaimonia, or the potential of it.

“He is also the type to benefit others but is ashamed to receive a benefaction; for the former is a mark of one who is superior, the latter of one who is inferior. He is disposed to return a benefaction with a greater one, since in this way the person who [benefitted him] will owe him[.] Those who are great-souled seem to remember whatever benefaction they have done to others, yet not those done to them.”

A proud sort.

“It belongs to the great-souled also to need nothing [...] and to be great [haughty?] in the presence of people of worth and good fortune, but measured toward those of a middling rank. To exalt oneself among the [great] is not a lowborn thing, but to do so among the [lowly] is crude, [like] using one’s strength against the weak.

[...] he is idle and a procrastinator except wherever either a great honor or a great deed is at stake; he is disposed to act in few affairs, namely, in great and notable ones. He is necessarily open in both hate and love, for concealing these things is the mark of a fearful person, as is caring less for the truth than for people’s opinion.

He necessarily speaks and acts in an open manner: he speaks freely because he is disposed to feeling contempt for others, and he is given to truthfulness, except inasmuch as he is ironic toward the many. And he is necessarily incapable of living with a view to another—except a friend—since doing is so slavish.”

A picture is forming now of an insufferable “big man,” but Aristotle has more to say:

“Slowness of movement seems to be the mark of a great-souled man, as well as a deep voice and steady speech for he who is serious about few things is not given to hastiness, nor is anyone ever vehement who supposes that nothing is great, whereas a shrill voice and quickness result from these things.”

The picture is now complete. The result of acquiring all the virtues, of practicing and mastering them, is an anti-social and charismatic type who appeared and wracked ancient Greece.

Aristotle’s system is now in peril.

Scholars have been plagued by the sudden pivot toward the Great Souled Man for centuries. That is not an exaggeration. Up until Book 4, Aristotle presented a coherent ethical system. Implied, was that this system would produce a strong and effective man (or woman, so far as I’m concerned). They would furthermore be balanced. Perfectly moderate. After all, his sense of virtue turns on occupying the “mean between extremes.” And not only would they be an effective and vibrant human, they’d also impact the polis, for the better.

We know from historical context and from Aristotle’s own work that a premium is placed on social life. The latter part of the Nicomachean Ethics are devoted to Justice and Friendship; to the capacity for living in a polis . . .

He tells us explicitly:

”He who is unable to live in society, or has no need because he is sufficient in himself, is a wild beast or a god.”

— Politics (1.2)

The Flourishing human, he or she who is Eudaimon, is socialized. They feel an affection for their fellow man, and work to better their overall lot. That is the promise of the Nicomachean Ethics; that if you are virtuous, you will become THAT.

Yet, his ultimate type, the infamous Great Souled Man, is a total megalomaniac. The reason lies in an error.

Early on, Aristotle determined the Ultimate Good, and did so quite simply. He said that whatever it is . . . must be a thing desired for itself, and not a thing desired to obtain something else. Money cannot be the ultimate good, because it is wanted to purchase a good life and ease. Nor pleasure, sought for contentment and joy; nor fame, nor power, nor health, nor knowledge—for all of these are for the sake of something else. There’s an angst in that; a yearning. Humans are fitfully striving for an unknown thing, and the pain of that is the human condition.

But we’ve already determined—along with Aristotle—what this Ultimate Good truly is. It is Flourishing (Eudaimonia). When we take all the things that humans pursue, what they’re actually chasing is Flourishing (mistakenly rendered as “Happiness” in English). The things we seek are thought to constitute or lead to that. Therefore, the sub-items and sub-concepts that would supposedly lead to Flourishing, are inferior or “external” goods. And one specific inferior good, rejected as the Ultimate Good by Aristotle . . . is Honor.

“But [...] honor seems to reside more with those who bestow it than with him who receives it; and we divine that the good is something of one’s own and a thing not easily taken away. Furthermore, people seem to pursue honor to convince themselves that they are good.”

— Nicomachean Ethics (1.5)

Honor is an inferior good, one sought—knowingly or not—for the sake of Flourishing (Eudaimonia). The Great Souled Man is flawed . . . VERY flawed . . . because the thing he pursues more than anything else is honor, not Eudaimonia.

If the Great Souled Man is Aristotle’s ultimate type, a pre-requisite in him is logic and rationality. Why then, is the ultimate type making a basic mistake? Why is he aiming for a lesser good, instead of the ultimate Good? How can he be Great Souled if his reasoning is so obviously impaired?

This becomes especially damning when we remind ourselves that the Nicomachean Ethics are a manual. They are essentially saying that if you practice “these virtues,” you will “Flourish.” But it turns out, according to Aristotle himself, that if you master the virtues you will want to die at war . . . in order to win a lesser Good: HONOR.

Plato has very few wins against Aristotle, but this is one: that he banished the poet from his Republic. Plato warns that the poet is capable of hijacking one’s capacity for Reason. He can seize you. He can turn off the reasoning part of your soul and unleash what Plato deems “dangerous.” It was surmised that his Philosopher-King and all of his perfect guardians could be led astray by verse; that poetry could prompt his Republic’s downfall.

He would seem vindicated then. Aristotle was seized by Homer, exactly as Plato had warned.

The Great Souled Man is Achilles in archetype. And we should wonder what conversations Aristotle had with his student, for Alexander the Great was a living Achilles. Both men were concerned with one thing above all else: Honor. And both men were incredibly anti-social as result, a trait that led them to atrocities.

Achilles, with his wanton killing; dragging a hero’s dead body by chariot. The betrayer of his own friends—who fought with actual gods, who killed the sons of gods, and brought ruin to everyone around him.

Alexander, another prolific killer; who terminated cities more enlightened than his own. At the peak of his megalomania, he even enslaved “fellow” Greeks. Alexander wept when there was nothing left to conquer, and left behind chaos in death.

The Great Souled Man is a homeric hero. Deep in his unconscious, Aristotle could not escape the outsized impact of Homer, the lordly poet. And nor is the Great Souled Man a constructive hero, like Hector. He is Achillean. He is so anti-social that when we read his constellation of traits and behaviors, we can only see him destroying a social order. And this is damning, because in the Politics, the sociability of a human being is paramount. They must be able to live in a community. Their presence must enhance it, better it, and protect it—and if they cannot live with their fellow man in such a way, they are either a wild beast or a god.

Having exposed Aristotle’s error, and having outlined where it came from, it remains to be asked if the idea is redeemable. After all, we can’t shake it. Something should happen if one has all the virtues. A certain type of person should emerge. And most important of all, they must be able to live in a Polis and benefit it; something Achilles and Alexander were both incapable of.

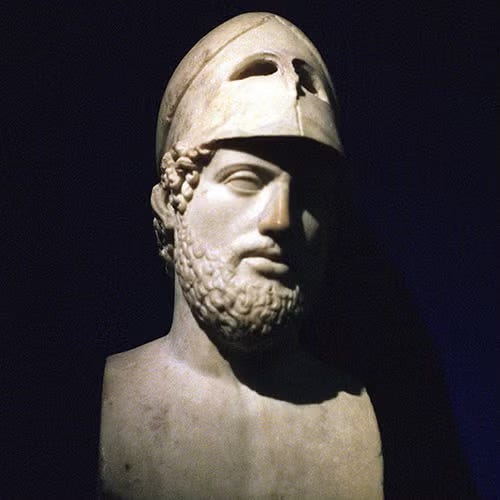

If there is anyone who neared all the Virtues; who occupied nearly every mean between extremes; who was Courageous, Temperate, Generous, Magnificent, Ambitious, Truthful, Just and all the rest . . . it was Pericles.

By Pericles, Athens went up in gold. The golden age of Athens, in fact, is squarely attributed to him. The public works are one thing; the Parthenon, Propylaea, the temple to Athena and Nike, the Erectheum and many more—all these brought about an awe. But the flowering of human potential meant more. Poets and philosophers thrived. The literacy rate exploded. What was a true and legitimate Direct Democracy expanded and made an effective populace. People, because of Pericles, Flourished.

It turns out the exercise of searching for a “Great Souled Man” is not futile, and that by removing the Homeric influence, we can arrive at a truly Aristotelian type. But what’s truly valuable is not the figure or the idea itself, but what it reveals by accident.

True Flourishing, is catalytic.

From this point on, we are reaching beyond Aristotle and are pulling from the Greek tradition broadly.

Before, we revealed that the word “Virtue” in English corresponds to the Greek Aretê. And that the word Aretê is better understood as “Excellence.” However, within this concept, the Greeks blended several things together. This prompted us to describe Aretê as being comprised of Rationality, Good Conduct, and Skillfulness (Technē). These three things in tandem produced an Excellent individual. And to the Greeks, an excellent individual was a Virtuous one. This distinction is important, because whether we are Christian or secular, we tend to associate Virtue with abstention; with not doing bad things. In the Greek mode, however, Virtue necessitates action and it implies a high level of competence. To us, Virtue has nothing to do with effectiveness . . . in fact, we tend to valorize the incompetent, because they are more likely to be “good,” in the sense that they don’t have the capacity for doing harm at all . . . and they naturally abstain from sin and vice (out of meekness or neuroticism).

Greek Virtue, then, is a type of human efficacy. Aristotle is of the idea that if one acquires the Virtues, they will Flourish automatically. This is not the case in my view. Right off, we can point to the Great Souled Man, who upon gaining the virtues acts like a Homeric hero. But we can also point to history.

Figures like Caesar, Napoleon and Hitler possessed Skillfulness to inhuman degrees. They also possessed several of the virtues, chief among them being Courage. All three are repulsive and were disastrous for mankind, but their Aretê is undeniable, for sure.

I would first assert that Aretê is not static, but is always in flux. That is to say that one’s Rationality, Good Conduct and Skillfulness can both grow and contract. Whether one Flourishes or not, then, would seem to depend on what their Aretê is aimed at. Caesar, Napoleon and Hitler all read like Aristotle’s Great Souled Man . . . and if we refigure Honor into the broad idea of pursuing one’s personal power and aggrandizement at all costs . . . especially over the community or polis . . . the idea starts to make sense. Obviously, as shown by the Great Souled Man and by these figures, Aretê directed at honor damages one’s Good Conduct the most, and slides one into a deficiency or excess (recklessness, stinginess, hubris, on and on).

But the example of Pericles reveals that if one’s Aretê is aimed at the community or polis, Flourishing will result. Not only one’s own Flourishing, but the Flourishing of the community in total. As a result, I assert that actual Eudaimonia can be measured by whether or not the figure is catalytic. Their activity should cause those around them to Flourish, which scales by their status and position in society. Beyond being stabbed to death, exiled, or committing suicide, we know that Caesar, Napoleon and Hitler were not Eudaimon because they terminated the Flourishing of millions (on top of their own).

By asserting that true Eudaimonia is ultimately catalytic, the Nicomachean Ethics become better integrated with the Politics (Aristotle’s other major work). It also completes the notion that there is an ultimate human end; one that cultivates something inherently individual, but that is also necessary for the whole.

But Flourishing is not simply for the demagogue or good leader, it is the universal Telos for all human beings, at every station of life.

I knew of a woman who wanted to move across the country to open a gym. A gym only for women. It would cater to their specific concerns, both physical and mental. Her family, being traditional, vehemently opposed this—since it was more proper, in their view, for her to simply settle down and get married. Nor did her family’s opposition remain verbal, they actively fought to sabotage and obstruct her.

Detaching from the emotional element here, this is another case-study in Eudaimonia. If she pursued this, and persisted through the hardship; through the uncertainty, financial contractions, and the sheer difficulty of starting a business, she would surely end up Flourishing. Not just financially, in the sense of common success, but likewise in the sense of character, improvement, and fulfillment. Furthermore, if she succeeded in this endeavor, it would have a catalytic effect first on tens of women; then hundreds; then thousands. This makes the cost of not pursuing her Telos very high (not only for herself, but for the unknowing many).

It is possible to conceive of one’s Telos as being obligated (by Nature at the very least), for its authentic cultivation would surely catalyze the many toward their own Telos as well. And if we are operating in a classical mode, THIS would be taken to be THE Good; that which you must devote your whole life to.